What happens to the human body in deep space?

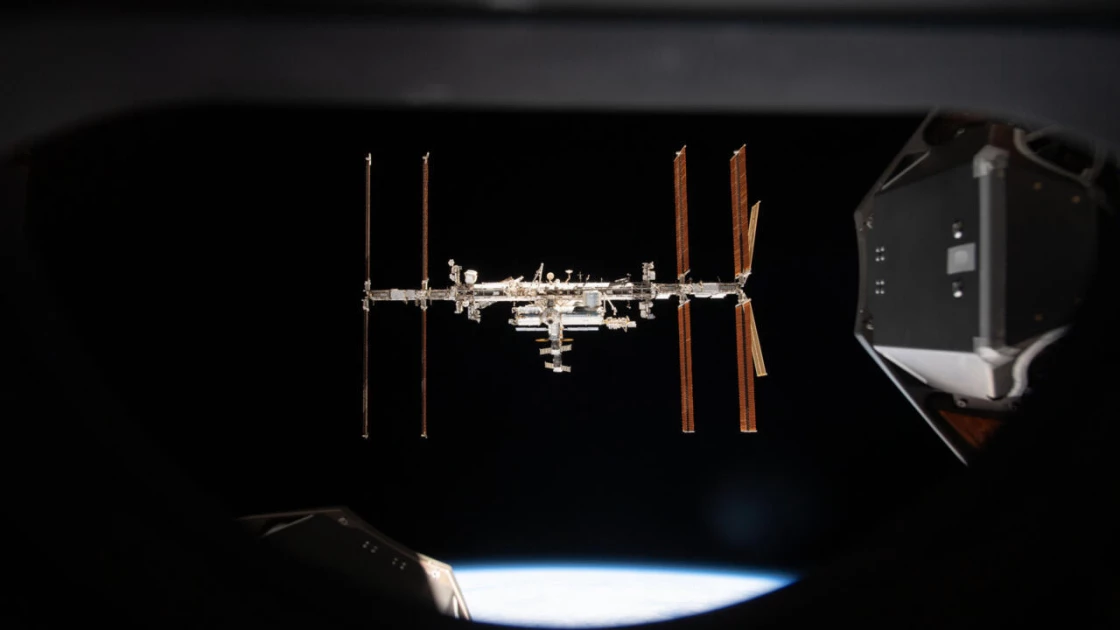

As astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams prepare to return home after nine months aboard the International Space Station (ISS), some of the health risks they've faced are well-documented and managed, while others remain a mystery © - / NASA/AFP/File

Audio By Vocalize

Bone and muscle

deterioration, radiation exposure, and vision impairment -- are just a few of

the challenges space travellers face on long-duration missions, even before

considering the psychological toll of isolation.

As US astronauts Butch

Wilmore and Suni Williams prepare to return home after nine months aboard the

International Space Station (ISS), some of the health risks they've faced are

well-documented and managed, while others remain a mystery.

These dangers will

only grow as humanity pushes deeper into the solar system, including to Mars,

demanding innovative solutions to safeguard the future of space exploration.

Despite the attention

their mission has received, Wilmore and Williams' nine-month stay is "par

for the course," said Rihana Bokhari, an assistant professor at the Center

for Space Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine.

ISS missions typically

last six months, but some astronauts stay up to a year, and researchers are

confident in their ability to maintain astronaut health for that duration.

Most people know that

lifting weights builds muscle and strengthens bones, but even basic movement on

Earth resists gravity, an element missing in orbit.

To counteract this,

astronauts use three exercise machines on the ISS, including a 2009-installed

resistance device that simulates free weights using vacuum tubes and flywheel

cables.

A two-hour daily

workout keeps them in shape. "The best results that we have to show that

we're being very effective is that we don't really have a fracture problem in

astronauts when they return to the ground," though bone loss is still

detectable on scans, Bokhari told AFP.

Balance disruption is

another issue, added Emmanuel Urquieta, vice chair of Aerospace Medicine at the

University of Central Florida.

"This happens to

every single astronaut, even those who go into space just for a few days,"

he told AFP, as they work to rebuild trust in their inner ear.

Astronauts must

retrain their bodies during NASA's 45-day post-mission rehabilitation program.

Another challenge is

"fluid shift" -- the redistribution of bodily fluids toward the head

in microgravity. This can increase calcium levels in urine, raising the risk of

kidney stones.

Fluid shifts might

also contribute to increased intracranial pressure, altering the shape of the

eyeball and causing spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS),

causing mild-to-moderate vision impairment. Another theory suggests that raised

carbon dioxide levels are the cause.

But in at least one

case, the effects have been beneficial. "I had a pretty severe case of

SANS," NASA astronaut Jessica Meir said before the latest launch.

"When I launched,

I wore glasses and contacts, but due to globe flattening, I now have 20/15

vision -- most expensive corrective surgery possible. Thank you,

taxpayers."

- Managing

radiation -

Radiation levels

aboard the ISS are higher than on the ground, as it passes through through the

Van Allen radiation belt, but Earth's magnetic field still provides significant

protection.

The shielding is

crucial, as NASA aims to limit astronauts' increased lifetime cancer risk to

within three per cent.

However, missions to

the Moon and Mars will give astronauts far greater exposure, explained

astrophysicist Siegfried Eggl.

Future space probes

could provide some warning time for high-radiation events, such as coronal mass

ejections -- plasma clouds from the Sun -- but cosmic radiation remains

unpredictable.

"Shielding is

best done with heavy materials like lead or water, but you need vast quantities

of it," said Eggl, of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Artificial gravity,

created by rotating spacecraft frames, could help astronauts stay functional

upon arrival after a nine-month journey to Mars.

Alternatively, a

spacecraft could use powerful acceleration and deceleration that matches the

force of Earth's gravity.

That approach would be

speedier -- reducing radiation exposure risks -- but requires nuclear

propulsion technologies that don't yet exist.

Future drugs and even

gene therapies could enhance the body's defences against space radiation.

"There's a lot of research into that area," said Urquieta.

Preventing infighting

among teams will be critical, said Joseph Keebler, a psychologist at

Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University.

"Imagine being

stuck in a van with anybody for three years: these vessels aren't that big,

there's no privacy, there's no backyard to go to," he said.

"I really commend

astronauts that commit to this. It's an unfathomable job."

Leave a Comment