OPINION: SHA/SHIF - Let’s dream a little, shall we?

File image of the SHA buildings in Nairobi. PHOTO | COURTESY

Audio By Vocalize

By

Paulie Mugure Mugo

Here’s

the dream:

A

young boy - let’s call him Justus - leaves his modest home somewhere in Kibra and

heads to a nearby compound a few meters down the road. He is carrying a yellow

ten-liter jerrycan, having been sent to the landlord’s home to fetch water

for his family’s needs.

But

as he hops playfully along, exchanging boyish banter with his neighborhood

pals, Justus suddenly finds himself smack in the path of a speeding

motorbike. Thwack! The violent thrust of hard steel against

the young boy’s tender frame leaves Justus lying motionless on the road,

jerrycan hurled several meters away and his thigh bone broken in two.

Screams

rent the air as a crowd gathers rapidly. In the ensuing melee, the motorbike

scampers off in a quick minute.

Meanwhile,

a sharp-witted neighbor recognizes the injured boy; she grabs her phone, dials

a four-digit number and an ambulance shortly arrives. Justus is whisked off to

the nearest suitable hospital, where he is admitted and treated carefully for

the next three months. Due to the seriousness of his injury, the hospital bill

quickly builds up, but his widowed mother is spared the indignity of begging

for help when his Ksh.300,000 bill is promptly settled courtesy of government

coffers.

End

of dream.

Believe

it or not, ladies and gentlemen, such an incident was narrated to me some days

ago by a lady named Mary*, an industrious, widowed mother of five who happens

to be Justus’ real-life mum. But her version didn’t end quite so well.

You

see, one afternoon in November 2019, Mary, who was employed as a househelp at

the time, had just finished frying chapatis for her bosses’ lunch, when her

mobile phone rang.

“Mary, kuja Mbagathi,” the caller had yelled

urgently. “Kimbia haraka..!”

On

the line was her neighbor, a friendly lady whose vegetable stall was just a few

meters from Mary’s Kibra home. Unbeknownst to Mary, little Justus, her

9-year-old son, had been heading to their landlord’s compound to fetch water,

when he had been slammed violently to the ground by a speeding boda boda. It

had been about half an hour since the incident occurred and the boy was now at

the Mbagathi County Referral Hospital. Mary pleaded with her neighbor to share

more details.

“Kimbia Mbagathi tu,” was the response; and no

one else, it seemed, was willing to explain what exactly had happened. So, the

terrified mother quickly downed her tools and ran to her son.

Mbagathi

Hospital, where young Justus had been rushed, is one of about 47 county

referral facilities located across Kenya and is managed by the county

government of Nairobi. Commissioned in 1956 by Sir Fredrick Crawford - the

deputy governor of Kenya at the time - Mbagathi was for a long time known as

Infectious Diseases Hospital (IDH), due to its initial role as an isolation

facility for the Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH). Having provided treatment

for diseases such as tuberculosis

and meningitis for almost fifty years,

the hospital began the transition to a fully-fledged district-level hospital in

1995. It is now one of Nairobi’s major referral facilities, handling almost

1,000 outpatient cases daily and boasting an inpatient capacity of 320 beds.

Kenya’s

healthcare system categorizes medical facilities from Level 1 to Level 6.

Mbagathi ranks at Level 5 and offers the wide range of services expected at

that level. So, when Mary got to the hospital that Saturday afternoon, she

found that an X-ray had already been done, revealing that her son’s left femur had been broken in two and that the lower

piece had moved a couple of inches upwards, with a portion of it lying parallel

to the other.

As

soon as the accident had occurred, Mary learned, a crowd had gathered rapidly

around her son, placed him hurriedly on a passing motorbike, and rushed him to

Mbagathi Hospital. That’s when she received that chilling call. But the good

Samaritans’ actions, while well-intentioned, had in all probability worsened the

condition of the child’s broken bone.

“Ilikuwa imeshikana hivi,” Mary

told me, folding her arms in front of her, each arm touching the other, with

one placed a few inches lower.

The

two pieces of bone would now have to be pulled apart and repositioned carefully

via skeletal traction, a contraption that combines pulleys, pins, and weights

to treat broken bones. Mary was advised that an urgent transfer to the Level 6

Kenyatta National Hospital was necessary.

Thus,

mother and son began a journey that would stretch two full months and eighteen days and leave Mary indebted in

the staggering amount of Ksh.257,944. It was more money than she had ever seen.

In

the almost 80 days that Justus lay at KNH, his leg strung up and strictly stationary, several hospital

staff inquired if anyone had captured details of the offending motorbike,

hoping, perhaps, to help bring its rider to

book.

But

in the crucial moments after the crash, the only thing that Mary’s kind

neighbor - and main witness - had seen, were the retreating backs of the boda

driver and his passenger, as they scrambled hastily off the ground, jumped back

on the motorbike and fled. And no one who had been in the crowd that day had

anything further to add. So, there was no hope of any kind of recompense from

that end.

Mary’s

monthly salary was Ksh.10,000 at the time and the last time she had contributed

to NHIF was six years earlier, when she had been formally employed by a

mid-sized trading company. Needless to say, she had no private insurance either.

So, the formidable buck stopped squarely at her work-worn feet.

“Plead

your case to a social worker at KNH,” someone advised when her son’s discharge

date drew near, suggesting that she garnish her story with tearful wails, if

necessary. “Toa machozi,” he

said.

So,

in anticipation of pleading for her son’s release, the desperate mother had

sought every single person or group willing to donate funds that she could

present to KNH as her contribution to the huge debt. Her plan was to humbly

request the hospital, through the good offices of their social workers, to

write off the balance once she paid part of the bill.

So,

at her request, Mary’s church kindly conducted a mini fund-raiser; Justus’

Kibra-based primary school chipped in; and her friends, family, and employer

gave what they could. Altogether, they were able to raise Ksh.30,000. And on

the day that she was to settle her son’s bill, Mary tucked the cash tightly

into her purse and made her way to the hospital dressed in her oldest and most

tattered clothes, hoping that her miserable appearance might aid her plea. To

her great relief, upon the recommendation of the social worker, the hospital

accepted the Ksh.30,000, and her child was discharged.

As

the debate on the recently launched Social Health Authority (SHA) has continued

to rage, I have been reminded of this story related to me by Mary, who now

works in my home. The truth is that, like Mary, the majority of households

in Kenya simply cannot afford to cater for the prolonged hospitalization of a

loved one; many could quite easily find themselves suddenly impoverished by the

critical illness of even one member of the family. We all

know what it means when we unexpectedly find ourselves in a WhatsApp group

named “Mary’s Medical Fund”, for example. Just a few days ago,

I found myself in one such group, having been roped in by an individual I last

saw in 2017.

So, now that NHIF, Kenya’s former national insurance, has been

put to bed and is resting quietly in peace, I thought I might as well educate

myself on the new, hotly-debated SHA.

The

concept of affordable, quality healthcare for all has been a long-held

aspiration for our country and was identified as a key priority in our Vision

2030 strategic plan. Accordingly, a number of initiatives have since been

established in an effort to strengthen healthcare provision in Kenya.

President Uhuru Kenyatta, for example, incorporated Universal

Health Coverage (UHC) as part of his administration’s Big Four Agenda. And in

December 2018, the former president launched a pilot UHC scheme in four counties

namely Kisumu, Isiolo, Nyeri and Machakos, and subsequently kicked off a

roll-out of the same to the other counties in February 2022.

But the current effort to attain UHC through the SHA, while

building on previous initiatives, represents the most aggressively ambitious

attempt yet.

The Social Health Authority (SHA), established in October 2023, aims to deliver UHC through three distinct funds, two of which will provide essential healthcare services free of charge to the Kenyan populace. These are the Public Healthcare Fund (PHC) and the Emergency, Chronic & Critical Illness Fund (ECCIF).

Through

the ECCIF, SHA aims to provide emergency services for all, such as accident,

critical illness and ambulance services. One can’t help but imagine that if an

ambulance had been available for young Justus, he may have been spared the

improper handling he suffered at the hands of eager but unskilled good

Samaritans that had very likely exacerbated his injury.

The

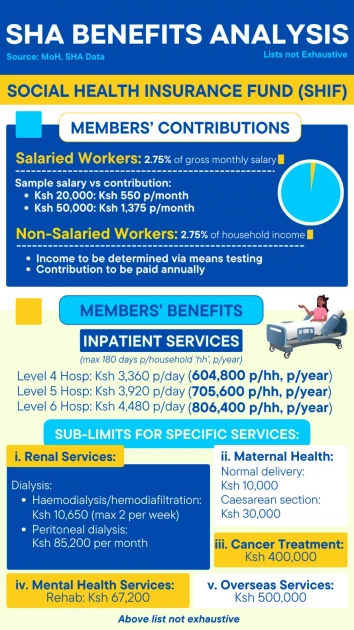

third fund is the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF), and contribution to this

is mandatory for all Kenyans at 2.75% of household income. This will be paid

either on a monthly basis by salaried employees, or on an annual basis by all

others. The minimum contribution will be Ksh.300 per month.

SHIF

will entitle paid-up households to a raft of services such as enhanced

outpatient services, medical imaging, maternal care, renal care, cancer

management, surgery and more.

Access

to inpatient services will be at Ksh.4,480 per day in Level 6 hospitals such as

Kenyatta Hospital, Moi, Kisii and Meru Teaching and Referral Hospitals, among

others. Theoretically,

had Mary been a member of SHIF and contributed the minimum Ksh.300 per month

commensurate with her salary, Justus’ Ksh.257,944 bill at KNH would easily have

been settled. Since SHIF caters for inpatient care for a maximum of 180 days

per household, per year, a good amount of cover would still have been left

available in case of any other hospitalization that year.

A survey of private Level 5 hospitals such as Mater Misericordiae, AAR Hospital, the Aga Khan and Nairobi Hospital shows that the general ward bed charges range from Ksh.8,200 to upwards of Ksh.11,000 per day. The SHIF contribution to this is set at Ksh.3,920 per day which is close to what NHIF formerly paid for similar facilities. Like its predecessor, SHA does not bar members from acquiring additional cover from private insurance companies to cover charges that may exceed its set limit.

Not

many nations worldwide have achieved truly successful universal health

coverage, and there have been undeniable challenges in the roll-out of our home-grown

SHA. Some issues may even persist for some time. However, I find myself

persuaded that, if properly implemented, SHA represents a huge leap forward in

healthcare provision for our country. And so, in the last few days, in hopeful

anticipation of better days, I have ensured that my entire household, and

Mary’s, have been registered with the SHA. We’re an optimistic lot around here.

In

October last year, when President William Ruto assented to four parliamentary

bills that paved the way for the implementation of SHA’s scheme, he stated

that as a country we had “reached a pivotal moment in our quest to reshape our

healthcare”, and that we now had a firm foundation for “the biggest change in

our healthcare system ever witnessed.”

I

am hopeful that his government will deliver on this promise, and that I will

not be forced to swallow this 2,185-word ode to hope. Nevertheless, I choose to

keep my indigestion tabs close by, just in case. And my 2027 vote.

Meantime,

I choose to dream.

*Names

have been changed.

[Paulie

Mugure Mugo is a published author and a co-founder of Eagles Leadership Network

(ELN), an initiative that trains and equips upcoming leaders in the area of

ethical governance.]

Leave a Comment