A legacy of uncertainty: The unresolved fate of Kenya’s six-hour president

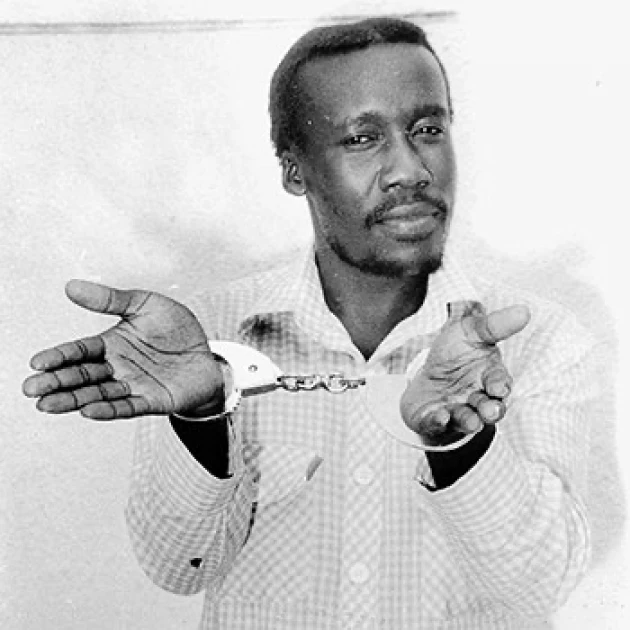

Hezekiah Ochuka Rabala, a Senior Private in the Kenya Air Force, is believed to have briefly led the country as president during a failed coup 37 years ago. Photo: File

Audio By Vocalize

In the quiet village of Nyakach Koguta in

Kisumu County lies the modest homestead of Hezekiah Ochuka Rabala, also known

as Awuor Onani. Once a Senior Private in the Kenya Air Force, Ochuka is

believed to have led Kenya as president for a mere six hours during an

attempted coup that still stirs controversy 37 years later.

The atmosphere in this secluded compound is a

mix of calm and tension, as questions linger about the fate of those involved

in the coup.

Ochuka’s cousin, Robert Akuro, sits in the

homestead surrounded by unused bricks and a mud-thatched house. With a sombre

expression, he recalls the story of the soldier who dared to challenge the late

President Daniel Moi’s regime.

Akuro’s face darkens as he tries to piece

together the events of that fateful day. He remembers August 1, 1982, the day

of the attempted coup, vividly.

"It was a Sunday morning," he

begins, "we were on the farm harvesting maize when we overheard a radio

announcement that the military had taken over the leadership of the country,"

Akura recalls.

At the time, the family had no idea that

their relative, Ochuka, was at the centre of the coup. They only knew that

he worked with the Air Force, but it never crossed their minds that he could be

the leader of such a bold move.

"As days went by, Ochuka’s name started

appearing in the newspapers as the coup leader," Akuro says, the shock

still evident in his voice.

The family’s concern grew when reports

surfaced that eleven soldiers had been killed for their involvement in the

coup. Ochuka’s father, Enoch Akuro, left their village of Nyabondo in Nyakach

for Nairobi, desperate to find his son. When he arrived, he was relieved to

learn that Ochuka was not among the dead.

"Many soldiers were killed, some with

guns still in their hands," Robert recounts. "But we later learned

that Ochuka, along with Oteyo Akumu and others, had escaped to Tanzania."

In Tanzania, the escapees sought asylum,

which complicated efforts to extradite them to Kenya.

"Plans to extradite Ochuka and his group

from Tanzania failed because they had sought asylum," Akuro explains.

Eventually, Ochuka was extradited to Kenya, detained, and charged with treason.

"While in the Kenyan prison, his sister,

Mary Odhiambo, his mother, his father and a lady named Linet Owira were the

only ones allowed to visit him," Akuro recalls.

After his sentencing, family visits became

rare, and Ochuka’s presence in their lives faded into the background.

"His case was handled by the court martial, and I vividly remember that the current Speaker of the National

Assembly, Moses Wetangula, was his lawyer," Akuro notes.

In 1987, the court ruled that Ochuka was to

be hanged. "I remember the day that news broke—it was devastating. Our

compound was filled with mourners, wailing in despair," Akuro says, the

memory still fresh in his mind.

Despite the grim sentence, the family never

saw Ochuka’s body, and according to Luo tradition, they held a ceremony to bury

something in his honour. However, government detectives disrupted the ceremony,

warning the family not to conduct any funeral rituals until they received

official confirmation of Ochuka’s death.

"The detectives asked who had brought

the news of Ochuka's death, and upon learning it was based on a rumour, they

ordered the gathering to be dispersed. Before leaving, they banned any

funeral-related ceremonies, insisting they could only be held after a thorough

investigation confirmed Ochuka's death and evidence, such as his belongings,

was provided—something that has yet to happen," Akuro laments.

The family’s quest for closure did not end

there. Akuro recalls how Ochuka’s mother once breached President Moi’s security

during his visit to Nyakach Girls, desperate to inquire about her son’s

whereabouts. She was met with a brutal response from the security forces, a

memory that haunted her until her death. "She died a sad and disturbed

woman," Akuro says, his voice heavy with sorrow.

What troubles the family most is the silence

of Ochuka’s former lawyer, Moses Wetangula.

"It’s been over thirty years, and we’ve

never received any tangible evidence confirming Ochuka’s death," Akuro

says.

"The worst part is that Wetangula is

still alive. How can he know nothing about the client he represented? We have

lived all these years in hope, but we still don’t know if Ochuka is dead or

alive."

Even after decades, the family holds on to

the hope that one day the government will reveal the truth about their son,

whether he is dead or still somewhere out there.

Leave a Comment